The profit of books is according to the sensibility of the reader; the profoundest thought or passion sleeps as in a mine, until it is discovered by an equal mind and heart. -Ralph Waldo Emerson, Society and Solitude, 1870

Thursday, December 13, 2012

Hat Full of Sky, by Terry Pratchett

Labels:

Education,

Fantasy,

Friendship,

Middle-Grade,

Nature,

Read more of this author

Wednesday, November 28, 2012

Witches Abroad, by Terry Pratchett

The concept of "stories" and what it takes to make an ending (ie: whether Cinderella, (or Emberella, as the case may be) gets married to the prince) is thoroughly drawn apart and put back together with enchanting and thoughtful twists. The idea that the people and their lives have to change with the times is pretty hard for one of the characters to swallow.

Mirrors are a powerful symbol and the concepts Pratchett creates surrounding their use are very creative and yet, as always, make complete sense.

Take note of all the things Granny Weatherwax tells Margret not to do.

There is some old-lady bedroom discussion that was quite forward, so for that reason this book goes on my 'not-squeaky-clean-therefore-not-recommended' list.

Labels:

Drama,

Education,

Fantasy,

Not Recommended,

Parenting

Tuesday, November 20, 2012

Going Postal, by Terry Pratchett

The idea of the golem carrying out instructions, no matter what, provided a lot of pondering material for me. So many situations are presented in the book that gave me a lot to think about with Mister Pump and his fellows.

The main character was a con-man in a former life, and his innate ability to read people and provide exactly what they need was instructive. There are so many fascinating characters with valuable outlooks on life.

The ideas presented by the wizards were incredible - and both modest and outrageous at the same time - "Not doing any magic at all was the chief task of wizards - not 'not doing magic' because they couldn't do magic, but not doing magic when they could and didn't. Any ignorant fool can fail to turn someone else into a frog. You have to be clever to refrain from doing it when you know how easy it is. There were places in the world commemorating those times when wizards hadn't been quite so clever, and on many of them the grass would never grow again."

The filthiness of the city Ankh-Morpork was something of a fairy tale to me until I visited New York City. Then I found that Pratchetts descriptions of how vile the pigeons are (based on their diet of eating things off the streets) made complete sense. There are places in the world where one can live and never have a desire to go barefoot outside. That was incomprehensible to me before I knew NYC.

"Words are important. And when there is a critical mass of them, they change the nature of the universe."

Wednesday, October 24, 2012

Something Wicked This Way Comes, by Ray Bradbury

I was fascinated by how different this was from Fahrenheit 451. Two completely different genres, and masterful execution in both categories.

This famous quote from Shakespeare took on new meaning after I finished this novel, which focuses heavily on time:

To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,There are tense and scary moments in this book and a parent should use judgement in allowing a child to read it, but I felt that it was not satanic or eery beyond reason - the author has a point to make about joy and sorrow, and a point to make about the seasons of our lives, and he makes these points exquisitely using the play of good and evil and the one caught between. It is a powerful story with a powerful message. I recommend this book especially to male tweens and fifty-somethings, and anyone who has either of those categories of people in their lives; but everyone will come away from this novel reminded of some valuable truths.

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

In one scene a father is looking out a second-floor window and sees his son and another boy:

"Look! he thought. Will runs because running is its own excuse. Jim runs because somthing's up ahead of him.Another contrast is drawn between the boys a few pages later,

"Yet, strangely, they do run together."

"The trouble with Jim was he looked at the world and could not look away. And when you never look away all your life, by the time you are thirteen you have done twenty years taking in the laundry of the world.This innocence vs. experience plays out time and time again throughout the book and has a huge influence on the paths the boys take. It's also interesting to note that Jim lives with his single mother, while Will has a mother and a father at home. I think Will is partly innocent because of his parents, and that his innocence and parental protection save him from wanting the same freedom Jim wants, and so he ends up in the better situation most of the time. Now, I may be biased because I identified more with Will, but that's how I felt.

"Will Halloway, it was in him young to always look just beyond, over or to one side. So at thirteen he had saved up only six years of staring."

Near the end of the novel Will and his father are looking for Jim -

"And Jim? Well, where was Jim? This way one day, that way the next, and . . . tonight? Whose side would he wind up on? Ours! Old friend Jim! Ours, of course! But Will trembled. Did friends last forever, then? For eternity, could they be counted to a warm, round and handsome sum?"

The 'bad guy' in this book is the Illustrated Man, who is covered with tattoos, and at once represents one person and a mass of monsters moving and breathing with one intent. When he (spoiler alert?) is defeated, it states

"[He], and his stricken and bruised conclave of monsters, his felt but half-seen crowd, fell to earth.

"There should have been a roar like a mountain slid to ruin.

"But there was only a rustle, like a Japanese paper lantern dropped in the dust."

Once the evil is wiped out, Will asks

"Dad, will they ever come back?"The main take-aways are that we can overcome evil (be it internal or external) and that it's okay to take time growing up, and then it's okay to be old. Life has a pattern and we follow it for a reason.

"No. And yes." Dad tucked away his harmonica. "No, not them. But yes, other people like them. Not in a carnival. God knows what shape they'll come in next. But sunrise, noon, or at the latest, sunset tomorrow they'll show. They're on the road."

"Oh, no," said Will.

"Oh, yes," said Dad. "We got to watch ou the rest of our lives. The fight's just begun."

...

"What will they look like? How will we know them?"

"Why," said Dad quietly, "maybe they're already here."

Both boys looked around swiftly.

But there was only the meadow, the machine, and themselves.

Will looked at Jin, at his father, and then down at his own body and hands. He glanced up at Dad.

Dad nodded, once, gravely. . .

It's very subtle, but I think the book ends just a few minutes after the boys reach the long-awaited age of 14.

Wednesday, October 17, 2012

Home Learning Year by Year, by Rebecca Rupp

I chose this book to get an idea of curriculum from preschool through kindergarten, so I only skimmed/read two chapters. I love, love, love that Rupp presents books to teach concepts, such as Benny's Pennies by Pat Drisson for understanding coins, or All About Seeds by Melvin Berger for basic botany concepts. There are hundreds of fabulous picture books listed for children to learn concepts from, and the trend continues with age-appropriate books throughout each grade.

This is a list for my personal use of the things I would like to make sure the child in my life learns:

PreK:

Crayons / Finger paint

Memorization

Tie shoes

Cut with scissors

Read

Addition and Subtraction

Hollidays

Famous People

Finger plays

Volume math with cups/measuring

Kindergarten level:

Art (identify color, shape, lines; discus famous works; experiment)

Music (rhythm, melody, harmony, listen to a range of genres, ID instruments by sight and sound)

Syllables

Sequence cards

Retell Stories

Group sets / take out wrong items

Tell digital and analog time, compare time (does it take longer to bathe or change into jammies?)

Right and Left

Math

Patterns

Count by 2s to 10, by 5s to 50

Count items and write the number

> < =

Ordinal positions (what came second?)

Concept of half

Know (+) and (-) signs

Invent and solve story problems

Money

Length, weight, capacity (longer than, taller than, more full, less full, rulers, scales, measuring cups, containers, standard and non-standard measures, books: Math Counts Series by Henry Pluck Rose)

Thermometer (hotter than / colder than)

Social Studies (history, geography, civics, economics, culture {family life at different times and places around the world})

Indians / Columbus / Pilgrims

Revolution (4th of July, Flag, national anthem)

Presidents (White House, Statue of Liberty)

Globe / continents

Maps (simple too: bedroom, house, yard)

Science: is a process

Nature

Sort/classify

Magnets

Light and shadow

Living/non-living

Deciduous/evergreen

Sun/soil/water

basics of photosynthesis

Needs of animals/babies/pets

5 senses / body

Earth (Soil/rock/water/air, seasons, weather)

Again, this list is for my personal use and does not represent the complete list of items Rupp presents for children in either the preK or K levels. The lists of books she includes with these concepts is a fabulous resource. Happy learning!

Monday, October 15, 2012

The Brain that Changes Itself, by Norman Doidge, M.D.

This was a fascinating and exceptionally informative read. Our brains are capable of so much if we know how to use them. My favorite take away was "Things that fire together wire together." It goes back to Pavlov's dogs, I suppose: If you ring a bell and present food, pretty soon the dogs will begin to salivate when they hear a bell because those things go together. This explains how people can wire their brains incorrectly (getting pleasure out of disgusting things, etc) and how it is 100% true that we can re-wire those things. It takes a lot of time and effort to re-wire reactions, but it can be intentionally and specifically done. The two most important factors for changing brain function are real intent (focusing and desiring the change) and oxytocin. Oxytocin makes the connections between neurons more easily broken. Oxytocin is a hormone that is released during happy/peaceful/loving times, stimulated by things such as touch, seeing pictures of your baby, intimate physical relationships, and eating.

So many of the maladies that face adults result from neurons being wired incorrectly as a child. Truly, the family is the central unit of society, and a family that functions properly has a much greater advantage in turning out children who will function properly in society.

Neuro plasticity can erase phantom limbs, reduce the effects of autism, strokes and ADD, cure retardation, masochism, pornography addictions, and obsessions, and increase the pleasure we get from physical and spiritual relationships. It affects every part of our lives and is a powerful aspect of our brains to have an understanding of. The "talking cure," or the benefits of using a psychologist, are proved through plasticity research.

I recommend skipping the disgusting depths of pornography discussed from pages 102-112.

Here are some quotes from the book that I want to remember:

Page 41-2: "Up through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries a classical education often included rote memorization of long poems in foreign languages, which strengthened the auditory memory (hence thinking in language) and an almost fanatical attention to handwriting, which probably helped strengthen motor capacities and thus not only helped handwriting but added speed and fluency to reading and speaking. Often a great deal of attention was paid to exact elocution and to perfecting the pronunciation of words. Then in the 1960s educators dropped such traditional exercises from the curriculum, because they were too rigid, boring, and "not relevant." But the loss of these drills has been costly; they may have been the only opportunity that many students had to systematically exercise the brain function that gives us fluency and grace with symbols. For the rest of us, their disappearance may have contributed to the general decline of eloquence, which requires memory and a level of auditory brainpower unfamiliar to us now. ... Today many of the most learned among us... prefer the omnipresent PowerPoint presentation--the ultimate compensation for a weak premotor cortex."

Page 213: "Everything your "immaterial" mind imagines leaves material traces. Each thought alters the physical state of your brain synapses and a microscopic level. Each time you imagine moving your finders across the keys to play the piano, you alter the tendrils in your living brain." This has powerful implications for positive self-talk/image and for pornography addicts. Things that fire together wire together, and we can change what we allow to fire together. Thoughts are the pathways to action. A beautiful and frightening truth.

Page 243: "Because our neuroplasticity can give rise to both mental flexibility and mental rigidity, we tend to underestimate our own potential for flexibility, which most of us experience only in flashes.

"Freud was right when he said that the absence of plasticity seemed related to force of habit."

Page 252: "This theory, that novel environments may trigger neurogenesis, is consistent with Merzenich's discovery that in order to keep the brain fit, we must learn something new, rather than simply replaying already-mastered skills.

... "Thus physical exercise and learning work in complementary ways: the first to make new stem cells, the second to prolong their survival."

Page 255: "Simply walking, at a good pace, stimulates the growth of new neurons."

Page 256: "Nothing speeds brain atrophy more than being immobilized in the same environment..."

Page 308: "Listening to an audio book leaves a different set of memories than reading does. A newscast heard on the radio is processed differently from the same words read in a newspaper." ... each medium creates a different sensory and semantic experience--and, we might add, develops different circuits in the brain."

Page 309: "The cost [of watching TV] is that such activities as reading, complex conversation, and listening to lectures become more difficult."

So many of the maladies that face adults result from neurons being wired incorrectly as a child. Truly, the family is the central unit of society, and a family that functions properly has a much greater advantage in turning out children who will function properly in society.

Neuro plasticity can erase phantom limbs, reduce the effects of autism, strokes and ADD, cure retardation, masochism, pornography addictions, and obsessions, and increase the pleasure we get from physical and spiritual relationships. It affects every part of our lives and is a powerful aspect of our brains to have an understanding of. The "talking cure," or the benefits of using a psychologist, are proved through plasticity research.

I recommend skipping the disgusting depths of pornography discussed from pages 102-112.

Here are some quotes from the book that I want to remember:

Page 41-2: "Up through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries a classical education often included rote memorization of long poems in foreign languages, which strengthened the auditory memory (hence thinking in language) and an almost fanatical attention to handwriting, which probably helped strengthen motor capacities and thus not only helped handwriting but added speed and fluency to reading and speaking. Often a great deal of attention was paid to exact elocution and to perfecting the pronunciation of words. Then in the 1960s educators dropped such traditional exercises from the curriculum, because they were too rigid, boring, and "not relevant." But the loss of these drills has been costly; they may have been the only opportunity that many students had to systematically exercise the brain function that gives us fluency and grace with symbols. For the rest of us, their disappearance may have contributed to the general decline of eloquence, which requires memory and a level of auditory brainpower unfamiliar to us now. ... Today many of the most learned among us... prefer the omnipresent PowerPoint presentation--the ultimate compensation for a weak premotor cortex."

Page 213: "Everything your "immaterial" mind imagines leaves material traces. Each thought alters the physical state of your brain synapses and a microscopic level. Each time you imagine moving your finders across the keys to play the piano, you alter the tendrils in your living brain." This has powerful implications for positive self-talk/image and for pornography addicts. Things that fire together wire together, and we can change what we allow to fire together. Thoughts are the pathways to action. A beautiful and frightening truth.

Page 243: "Because our neuroplasticity can give rise to both mental flexibility and mental rigidity, we tend to underestimate our own potential for flexibility, which most of us experience only in flashes.

"Freud was right when he said that the absence of plasticity seemed related to force of habit."

Page 252: "This theory, that novel environments may trigger neurogenesis, is consistent with Merzenich's discovery that in order to keep the brain fit, we must learn something new, rather than simply replaying already-mastered skills.

... "Thus physical exercise and learning work in complementary ways: the first to make new stem cells, the second to prolong their survival."

Page 255: "Simply walking, at a good pace, stimulates the growth of new neurons."

Page 256: "Nothing speeds brain atrophy more than being immobilized in the same environment..."

Page 308: "Listening to an audio book leaves a different set of memories than reading does. A newscast heard on the radio is processed differently from the same words read in a newspaper." ... each medium creates a different sensory and semantic experience--and, we might add, develops different circuits in the brain."

Page 309: "The cost [of watching TV] is that such activities as reading, complex conversation, and listening to lectures become more difficult."

Thursday, October 4, 2012

You Know When the Men Are Gone, by Sibohan Fallon

I loved this book, but beware strong language used in military (and family) settings. This book will leave you inspired by the incredible sacrifice that is made every day on your behalf. This

is a collection of short stories that all have common characters (so

fun!) and messages about current military life (not so fun, but very

worthwhile).

I have an immediate family member who served in the armed forces for several years and can personally attest to many of the facets and facts shared in this book, and willingly believe the rest. This is not a book that one can convey the message of - it's one that simply needs to be read and understood by the millions of Americans who have little or no idea what our service-men and -women and their families go though every day. It was powerfully moving.

In a world where it is normal for a thousand men pack their bags, meet on a parade field, and then disappear for an entire year... (p9)

She wanted to worry about ordinary things like whether her husband forgot his lunch or got a bonus, not that he might get shot or that he'd be crossing a street in Baghdad and never get to the other side. (p 22)

He glanced up in time to see Staff Sergeant Torres, on of the most laid-back guys he knew, walk straight over to the private and stomp the radio to smithereens.The private leaned back in his chair to get away from flying bits of plastic. Nick and two other soldiers moved in close, ready to pull the men apart if Staff Sergeant Torres planned on smashing the private's face as well.Instead Torres looked down at the shards under his boots. "I'll pay for that," he said, then turned and walked back to his tent.None of the men looked at each other, as if refusing to acknowledge what they had witnessed. They knew there was only on thing that would make a guy snap like that, make him want to crush those words out of existence, and it didn't have a [darn] thing to do with life in Iraq. (p 177)

The themes are adult. The moods are somber. The feelings are overwhelming. The effect awakens the reader to understanding and gratitude.

Monday, October 1, 2012

Austenland and Midnight in Austenland, by Shannon Hale

Not recommended due to the "flame in the veins" factor. I've been told Austenland is mild for Chic Lit, but it doesn't interest me to get those feelings from reading.

Austenland is a beautiful story of finding oneself and breaking out of a self-imposed mold. The flames are limited to a few make-out sessions.

Midnight in Austenland was a fun murder-mystery romance in a modern Agatha Christie style, but the main character was quite a bit more open about her feelings and thoughts about others' feelings throughout the book. There is value in the story of a divorced woman coming to terms with her new life/love life, but I fell any benefit from the story is more than negated.

While I do not recommend reading the novel, I did find several things in it that I pondered:

Austenland is a beautiful story of finding oneself and breaking out of a self-imposed mold. The flames are limited to a few make-out sessions.

Midnight in Austenland was a fun murder-mystery romance in a modern Agatha Christie style, but the main character was quite a bit more open about her feelings and thoughts about others' feelings throughout the book. There is value in the story of a divorced woman coming to terms with her new life/love life, but I fell any benefit from the story is more than negated.

While I do not recommend reading the novel, I did find several things in it that I pondered:

- On page 68 Hale comments "Even stories need a chance to sleep." I thought that was interesting from all sorts of view points, especially given that I often read a story in one sitting.

- A fun analogy on page 84 about murderers: "She would make a horrible murderer, more afraid of her victims than they were of her, a feeble spider trembling on her web. Stay away, flies! Please, stay away!"

- Another thought-provoking nature analogy I found on page 116: "Wind made everything opaque--wind made everything move." The whole paragraph about the differences between wind in the city and wind in the country was beautiful and ominous.

- She is drawing the silhouette of a gentleman and thinks, "It was an odd exercise. While she worked, he was free to gaze upon her, but she could only observe his shadow. She supposed that was always true--he saw her, the real Charlotte, while all she knew of him was the shadow of himself, this character he played. The thought gave her a shiver." (p 131)

- A final thought provoking moment from page 180 - she remembers playing chase with her mother in childhood: "Upon the shout of "Safe, safe!" any non-carpeted place automatically would become safe--a chair, a stool, a bed, a book, a blanket. They'd need a moment to know they were okay, but they'd never stay still for long. Seconds later, they'd take off again, hoping Mom was on their heels. / What fun was safe?" An ominous memory in the middle of a murder mystery...

Saturday, September 15, 2012

River Secrets and Forest Born, by Shannon Hale

I loved that River Secrets is written from a male's point of view. There is not enough good literature for young men out there. Razo seems to have a good head on his shoulders and learns many valuable lessons in the course of the story, despite his not being in possession of one of the amazing gifts that grace Shannon Hale's world of Bayern. A girl does straddle him with no good intentions, but he is uncomfortable and works his way through the situation.

Razo's sister, Rin, narrates Forest Born. The book is not what I expected. The gift works differently than anyone expects and creates a more beautiful balance in Rin's life than any of the other gift-bearers will be able to enjoy.

At one point some women are traveling without many supplies and they enter a house with fresh-baked bread. "That was the smell of home, and her ma, and the warm cottage when rainstorms seethed outside. It was a hard, hard thing to lose a home full of bread and Ma."

Later Rin and Razo have a tough decision to make, and Rin decided "She would risk herself. It was her gift to give." That is a beautiful statement of selflessness and is very characteristic of the woman Rin is becoming.

One of Razo's comments also struck me: "I'm not the smartest boy, I know that. Maybe that's not such a bad thing--smarts seem like a load of fancy clothes that you have to wear all the time, and they're heavy and rip easily even though you're supposed to keep them clean. A hassle, that's what that is." There are different kinds of 'smart' and Razo has his own, as he proves in the following sentences, but the idea that smart people feel they have to 'put on' for others is an interesting one to ponder. If you are smart there are things you can draw from that, and if you feel you are not, there is also a valuable lesson in that.

I felt that Forest Born was not quite as well written - there were a couple cheesy moments and a few crossed facts, but the core knowledge that Rin gains through the events in the book are a powerful and long accepted truth that will better any young adult who reads about it.

Spoiler alert: Rin learns that the trees act like a mirror, reflecting herself to her. When something ugly is in her soul or has marred her actions, she cannot find peace in the trees because she does not have peace within herself. She learns that she must repent to find peace again. This is important is a complex and powerful way. Where much is given, much is required.

Razo's sister, Rin, narrates Forest Born. The book is not what I expected. The gift works differently than anyone expects and creates a more beautiful balance in Rin's life than any of the other gift-bearers will be able to enjoy.

At one point some women are traveling without many supplies and they enter a house with fresh-baked bread. "That was the smell of home, and her ma, and the warm cottage when rainstorms seethed outside. It was a hard, hard thing to lose a home full of bread and Ma."

Later Rin and Razo have a tough decision to make, and Rin decided "She would risk herself. It was her gift to give." That is a beautiful statement of selflessness and is very characteristic of the woman Rin is becoming.

One of Razo's comments also struck me: "I'm not the smartest boy, I know that. Maybe that's not such a bad thing--smarts seem like a load of fancy clothes that you have to wear all the time, and they're heavy and rip easily even though you're supposed to keep them clean. A hassle, that's what that is." There are different kinds of 'smart' and Razo has his own, as he proves in the following sentences, but the idea that smart people feel they have to 'put on' for others is an interesting one to ponder. If you are smart there are things you can draw from that, and if you feel you are not, there is also a valuable lesson in that.

I felt that Forest Born was not quite as well written - there were a couple cheesy moments and a few crossed facts, but the core knowledge that Rin gains through the events in the book are a powerful and long accepted truth that will better any young adult who reads about it.

Spoiler alert: Rin learns that the trees act like a mirror, reflecting herself to her. When something ugly is in her soul or has marred her actions, she cannot find peace in the trees because she does not have peace within herself. She learns that she must repent to find peace again. This is important is a complex and powerful way. Where much is given, much is required.

Labels:

Drama,

Education,

Fantasy,

Friendship,

Middle-Grade,

Nature,

Read more of this author

Wednesday, September 5, 2012

The Glass Castle, by Jeannette Walls

A beautiful, ugly, and moving story of "real life." Jeannette details the fun of her childhood, moving from town to town, leaving the creditors behind. When she and her siblings started going to school they figured out that life for most people was not like the game their mother played with them (ie: "Our new home was one of the oldest in town, Mom proudly told us, with a real frontier quality to it.")

Jeanette Wells tells an incredible story that takes their family across the nation and through the depths of poverty. She eventually becomes a NY Time Bestselling author, and the story of her journey into the real world is incredible enough to be almost unbelievable.

There is some moral depravity in the book, but it is discussed in a matter-of-fact way, and in such a way as to be valuable to those who might be embarking on the world for themselves. There is a plentiful amount of swearing from the father throughout the book.

Spoiler alert: don't read the remainder of this post if you don't want the plot revealed.

I understand that there are many people who live in poverty because they have to. I was disgusted that the mother allowed her children to paw through the school garbage to find food their friends had thrown away, when she had inherited land that she chose not to sell. Even if it is a Family Law that land doesn't get sold, you sell your land to shelter, feed and clothe your children. It's just what you do. Even if you don't know how much land there is, where it is, or what it is worth, you find out and sell it.

I struggle, as does Jeanette, to understand her mother, who had no comprehension that motherhood is a divine calling and one of the most important, rewarding, and fulfilling things that can be done on this earth. Mother would rather paint (and invest in paints, mind you) than care for or attend her children. I personally am all about children being independent and learning to do things for themselves. Half of her behavior toward her children when they were little was not shocking to me at all. But during that time they at least had food in their tummies and a warm place to sleep. The way she abandoned them when they were old enough to scrounge for themselves was appalling to me. That she ate food herself instead of sharing it with her children, slept in a warmer, drier room, and quit the job that was their only sustenance because she wanted to paint more - just made me ache for the children, ache in the depths of my heart and soul.

The climax of the book, to me, occurred when Jeanette was in college. Her parents had followed the four kids to New York. The kids all worked and lived in real apartments and cared about the younger ones enough to help them get started in their lives there. The parents were homeless and liked it that way.

"You can't just live like this," Jeanette told her mom.

"Why not?" Mom said. "Being homeless is an adventure." And they stayed that way, despite their children offering to help them in various ways.

Then Jeanette had the following experience in class:

One day Professor Fuchs asked if homelessness was the result of drug abuse and misguided entitlement programs, as the conservatives claimed, or did it occur, as the liberals argued, because of cuts in social-service programs and the failure to create economic opportunity for the poor? Professor Fuchs called on me.

I hesitated. "Sometimes, I think, it's neither."

"Can you explain yourself?"

"I think that maybe sometimes people get the lives they want."'Professor Fuchs questions her further, and she says that if some people just worked they would be fine.

Professor Fuchs walked around from behind her lectern "What do you know about the lives of the underprivileged?" she asked. She was practically trembling with agitation. "What do you know about the hardships and obstacles that the underclass faces?"

The other students were staring at me.

"You have a point," I said.At the time I read it, I was infuriated that she was too worn out from her life to argue the truth of her stance. But she took care of it - she has argued it in a much more powerful way through this eye-opening, heart-rending, bestselling novel.

Saturday, September 1, 2012

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, by James Joyce

If you're not a big fan of the stream-of-consciousness writing style, this book may not be for you. It's a very inside-his-head portrait of the high school and college years of this young man. It includes his fall into moral sins, those of masturbation and fornication, and the deep despair his Catholic school drives into him about the peril of his soul. There are some gratuitous descriptions of his feelings during his encounters. He repents and forsakes his sinning, but later also forsakes God.

There are many bits of wisdom to be gleaned. On page 76 he remembers "Even that night as he stumbled homewards along Jones's Road he had felt that some power was divesting him of that sudden woven anger as easily as a fruit is divested of its soft ripe peel." The power of exercise and nature to relieve our negative emotions and draw us closer to God.

There is also a fascinating discussion of aesthetics and beauty near the end of the novel, including this description of 'the enchantment of the heart':

The instant wherein that supreme quality of beauty, the clear radiance of the estheic image, is apprehended luminously by the mind which has been arrested by its wholeness and fascinated by its harmony is the luminous silent stasis of esthetic pleasure, a spiritual state very like to that cardiac condition which the Italian physiologist Luigi Galvani, using a phrase almost as beautiful as Shelley's, called the enchantment of the heart.

There are many bits of wisdom to be gleaned. On page 76 he remembers "Even that night as he stumbled homewards along Jones's Road he had felt that some power was divesting him of that sudden woven anger as easily as a fruit is divested of its soft ripe peel." The power of exercise and nature to relieve our negative emotions and draw us closer to God.

There is also a fascinating discussion of aesthetics and beauty near the end of the novel, including this description of 'the enchantment of the heart':

The instant wherein that supreme quality of beauty, the clear radiance of the estheic image, is apprehended luminously by the mind which has been arrested by its wholeness and fascinated by its harmony is the luminous silent stasis of esthetic pleasure, a spiritual state very like to that cardiac condition which the Italian physiologist Luigi Galvani, using a phrase almost as beautiful as Shelley's, called the enchantment of the heart.

Though I don't recommend the entire book, the discussion of aesthetics was decidedly engaging to me and I recommend it to any who enjoy such discussions. It began on page 198 in my copy of the novel, with the statement "Aristotle has not defined pity and terror," and ends on page 209 with "The rain fell faster." I don't agree with the conclusion drawn of this discussion in the book, but the discussion itself was enlightening.

Labels:

Classics,

Education,

Friendship,

Nature,

Not Recommended

Monday, August 27, 2012

The Call of the Wild, by Jack London

I was struck by the wisdom of God in pronouncing the Sabbath day a day of rest. Many of the problems of fatigue and disorganization in this book could have been solved and even turned for the better by observing the Sabbath. Buck, as our main character is known throughout most of the novel, is quite literally run until he gives out. He starts as a house dog, king of his domain, and learns his place and how to survive in the wild.

Buck's adjustment to survival in the wild involves "the decay or going to pieces of his moral nature, a vain thing and a handicap in the ruthless struggle for existence. (p24)" The problem with this is that there is no line drawn then, and dogs are torn apart by other dogs, or teased mercilessly until their spirits break. So it is with man, and the morality must exist and bar us from crossing those lines.

At one point Buck has an "ideal master. Other men saw to the welfare of their dogs from a sense of duty and business expediency; he saw to the welfare of his as if they were his own children, because he could not help it. And he saw further. He never forgot a kindly greeting or a cheering word, and to sit down for a long talk with them... was as much his delight as theirs. (p76-77)" What a model for parenthood! Should we not, as parents, be unable to help the love and care we give, and delight in discussion with our children! How they will love and honor us if we could but be so respectful and loving.

Though Buck is not close to death at the time this quote is given, it struck me as a sort of eulogy, complex and beautiful:

(Spoiler alert, through the end:) There are two levels of "wild" addressed in this book, the first a transition from a domestic home (the 'law of love and fellowship') to survival as a sled dog (where the 'law of club and fang' rules). Buck eventually finds love and fellowship in the northern sled dog lands, and I think it is this return to peaceful living that enables him to hear within himself the call of the true wild, that of the dogs who have been running the earth fending for themselves since creation. He follows a wolf for quite some time, but then remember his master and the love and fellowship they share. He turns back.

Buck's adjustment to survival in the wild involves "the decay or going to pieces of his moral nature, a vain thing and a handicap in the ruthless struggle for existence. (p24)" The problem with this is that there is no line drawn then, and dogs are torn apart by other dogs, or teased mercilessly until their spirits break. So it is with man, and the morality must exist and bar us from crossing those lines.

At one point Buck has an "ideal master. Other men saw to the welfare of their dogs from a sense of duty and business expediency; he saw to the welfare of his as if they were his own children, because he could not help it. And he saw further. He never forgot a kindly greeting or a cheering word, and to sit down for a long talk with them... was as much his delight as theirs. (p76-77)" What a model for parenthood! Should we not, as parents, be unable to help the love and care we give, and delight in discussion with our children! How they will love and honor us if we could but be so respectful and loving.

Though Buck is not close to death at the time this quote is given, it struck me as a sort of eulogy, complex and beautiful:

He was older than the days he had seen and the breaths he had drawn. He linked the past with the present, and the eternity behind him throbbed through him in a mighty rhythm to which he swayed as the tides and seasons swayed. (p79)

(Spoiler alert, through the end:) There are two levels of "wild" addressed in this book, the first a transition from a domestic home (the 'law of love and fellowship') to survival as a sled dog (where the 'law of club and fang' rules). Buck eventually finds love and fellowship in the northern sled dog lands, and I think it is this return to peaceful living that enables him to hear within himself the call of the true wild, that of the dogs who have been running the earth fending for themselves since creation. He follows a wolf for quite some time, but then remember his master and the love and fellowship they share. He turns back.

For the better part of an hour the wild brother ran by his side, whining softly. Then he sat down, pointed his nose upward, and howled. It was a mournful howl, and as Buck held steadily on his way he heard it grow faint and fainter until it was lost in the distance. (p99)So Buck is not able to embrace the wild until his fellowship with man ceases to exist. What a blessing that in the true gospel of Jesus Christ we are able to take our families back with us when we return to God.

Thursday, August 23, 2012

Wuthering Heights, by Emily Bronte

An abyss of blackness, child abuse, and misguided souls, with twinkling lights of beauty and peace scattered throughout. The writing is powerful and the resolution stirring and complete. When life is stormy it is hard to see the precious bits of goodness in it, but they are the only thing to get us through.

Mrs. Dean, a housekeeper, is the primary narrator of the story. On page 76 the new master of the house asks her to tell the story, observing that she has

As a bit of background for this quote (p183), Edgar Linton really is significantly "less" than Heathcliff, who has depth and breadth that Edgar is neither interested in, nor comprehends. Also, Emily Bronte is sometimes accused of being too flowery or overbearing in these moments when speakers bare their souls, but her characters are larger than life, the epitome of themselves, and I never wanted for belief (or at least, I knew the characters absolutely believed). It may be a disservice to provide this quote to readers who haven't enjoyed the first portion of the novel, for you surely cannot appreciate it nearly as much if you had read it in context, but I include it here for myself too. Heathcliff is speaking:

Mrs. Dean has enough respect for both parties, interestingly enough, that on page 207 when she observed

Again, this quote (p213) is not much exaggerated:

There are several reviews published in the back of the novel. I found this unsigned review (p435) from The Examiner in January 1848 to be meaningful:

Mrs. Dean, a housekeeper, is the primary narrator of the story. On page 76 the new master of the house asks her to tell the story, observing that she has

"no marks of the manners which I am habituated to consider as peculiar to your class. I am sure you have thought a great deal more than the generality of servants think. You have been compelled to cultivate your reflective faculties for want of occasions for frittering your life away in silly trifles."Mrs. Dean attributes it to having

"undergone sharp discipline, which has taught me wisdom; and then, I have read more than you would fancy ... you could not open a book in this library that I have not looked into, and got something out of also."

As a bit of background for this quote (p183), Edgar Linton really is significantly "less" than Heathcliff, who has depth and breadth that Edgar is neither interested in, nor comprehends. Also, Emily Bronte is sometimes accused of being too flowery or overbearing in these moments when speakers bare their souls, but her characters are larger than life, the epitome of themselves, and I never wanted for belief (or at least, I knew the characters absolutely believed). It may be a disservice to provide this quote to readers who haven't enjoyed the first portion of the novel, for you surely cannot appreciate it nearly as much if you had read it in context, but I include it here for myself too. Heathcliff is speaking:

"You think she has nearly forgotten me?" he said. "Oh, Nelly! you know she has not! You know as well as I do, that for every thought she spends on Linton, she spends a thousand on me! ... And then, Linton would be nothing, nor Hindley, nor all the dreams that ever I dreamt. Two words would comprehend my future--death and hell: existence, after losing her, would be hell. Yet I was a fool to fancy for a moment that she valued Edgar Linton's attachment more than mine. If he loved with all the powers of his puny being, he couldn't love as much in eighty years as I could in a day. And Catherine has a heart as deep as I have: the sea could be as readily contained in that horse-trough, as her whole affection be monopolized by him! Tush! He is scarcely a degree dearer to her than her dog, or her horse. It is not in him to be loved like me: how can she love in him what he has not?"

Mrs. Dean has enough respect for both parties, interestingly enough, that on page 207 when she observed

"on the floor a curl of light hair, fastened with a silver thread; which, on examination, I ascertained to have been taken from [Catherine's locket]. Heathcliff had opened the trinket and cast out its contents, replacing them by a black lock of his own. I twisted the two, and enclosed them together."

Again, this quote (p213) is not much exaggerated:

"He's not a human being," she retorted; "and he has no claim on my charity. I gave him my heart and he took and pinched it to death, and flung it back to me. People feel with their heart, Ellen: and since he has destroyed mine, I have not power to feel for him."I took some time to ponder the truth of this statement, then the power of the atonement. Feeling is only possible again when our heart has been changed by the Savior.

There are several reviews published in the back of the novel. I found this unsigned review (p435) from The Examiner in January 1848 to be meaningful:

We ... willingly trust ourselves with an author who goes at once fearlessly into the moors and desolate places, for his heroes; but we must at the same time stipulate with him that he shall not drag into light all that he discovers, of coarse and loathsome. ... It is the province of the artist to modify and in some case refine what he beholds in the ordinary world.This again refers to how true the characters are to their own form - nothing is hidden of the alcoholism or the verbal, emotional, and physical abuse doled out. As my first paragraph stated, this book is sometimes an abyss of blackness, child abuse, and misguided souls, but twinkling lights of beauty and peace are scattered throughout, most notably in the form of kind or wise souls and the beauties of nature. Light and goodness are ours for the taking, even while in a storm.

Saturday, August 18, 2012

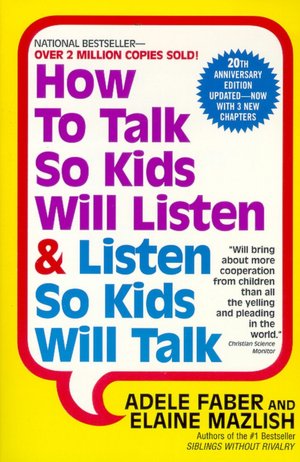

How to talk so Kids Will Listen & Listen so Kids will Talk, by Faber and Mazlish

An excellent book with very relevant strategies. The authors raised 6 children between them and never used a time out. That is very appealing to me, though I haven't been able to switch gears quite yet. I recommend, as they do, taking time to read each chapter and implement the skills (I've had the book about 10 weeks now). If you need a refresher (or are in a hurry) you can read through the cartoons and checklists and be back on your feet with the program in a few minutes.

"Practical, sensible, lucid... the approaches Faber and Mazlish lay out are so logical you wonder why you read them with suach a burst of discovery." -Family Journal

I agree with that statement completely. Everything in the book is common (or uncommon) sense, and based on respecting everyone. This method works for all ages and works along with Love and Logic, my favorite way to approach children from my teaching years.

Loved it!

"Practical, sensible, lucid... the approaches Faber and Mazlish lay out are so logical you wonder why you read them with suach a burst of discovery." -Family Journal

I agree with that statement completely. Everything in the book is common (or uncommon) sense, and based on respecting everyone. This method works for all ages and works along with Love and Logic, my favorite way to approach children from my teaching years.

Loved it!

Friday, August 17, 2012

Fahrenheit 451, by Ray Bradbury

The poor man, Montag, has an awful life, but maybe everybody in the book does. (Everyone uses sleeping pills, at any rate.) Such is the truth in any dystopian novel though. This one particularly highlights the importance of every person being educated and loving learning, especially through books. Montag is a fireman, in a time when houses are fireproof. His job is to go burn those houses that have books inside them. This did not start as a government mandate though, the people gradually stopped using books and eventually turned against them. Fahrenheit 451 is the temperature at which paper burns.

One day on the way home he meets his new neighbor, Clarise, who is the only happy person in the novel. She lives in a world her own and actually sees things around her and thinks. After they've known each other awhile, they have this exchange:

"Why is it," he said, some time, at the subway entrance, "I feel I've known you so many years?"

"Because I like you," she said, "and I don't want anything from you. And because we know each other."

An older man in the community who grew up with books and still loves them describes the three things missing from the people in that day. Lack of these three things led to the demise of the printed word: quality books, the leisure to digest them, and the right to carry out actions based on what we learn from the interaction of the first two. During the discussion on those three points this gentleman says "Books can be beaten down with reason. But with all my knowledge and skepticism, I have never been able to argue with a one-hundred-piece symphony orchestra..." I love that quote. Music is so powerful, but it is also ephemeral. The truth cuts both ways.

Later when Montag has some time to slow down and think, "He saw the moon low in the sky now. The moon there, and the light of the moon caused by what? By the sun, of course, and what lights the sun? Its own fire. And the sun goes on, day after day, burning and burning. The sun and time. The sun and time and burning. Burning. The sun and every clock on the earth. It all came together and became a single thing in his mind. After a long time... he knew why he must never burn again in his life. The sun burnt every day. It burnt Time. The world rushed in a circle and turned on its axis and time was busy burning the years and the people anyway, without any help from him. So if he burnt things with the firemen and the sun burnt Time, that meant that everything burnt! One of them had to stop burning. The sun wouldn't, certainly. So it looked as if it had to be Montag and the people he had worked with... The world was full of burning of all types and sizes." What do I burn? How do I burn? What things in my life do I need to alter to become, instead, one who does "the saving... the putting away... the keeping"?

At one point Montag leaves the city and finds a kind of fire he never knew: "That small motion, the white and red color, a strange fire because it meant a different thing to him.

It was not burning. It was warming.

... He hadn't known fire could look this way. He had never thought in his life that it could give as well as take. Even its smell was different."

There are several afterwards by the author in the book. He discusses censorship and other 'burning' of his own works, and shares his thoughts on digression, which I found interesting and will share here. "Digression is the soul of wit. Take philosophic asides away from Dante, Milton, or Hamlet's father's ghost and what stays is dry bones. Laurence Sterne said it once: Digressions, incontestably, are the sunshine, the life, the soul of reading! Take them out and one cold eternal winter would reign in every page. Restore them to the writer--he steps forth like a bridegroom, bids them all-hail, brings in variety and forbids the appetite to fail." This caused me no little reflection, and I am resolved to notice the use of digression more in my reading.

Friday, August 10, 2012

The Three Musketeers, by Alexandre Dumas

What delightful intrigue! And the four men are such honorable fellows, except when they're not, and they always tell the truth, except when they don't, and the subject of a mistress enters into 90% of the conversations, it seems, and it was normal at this time period. One of the explanatory notes on this topic was very interesting to me, stating that the eldest son inherited the family fortune (which I knew) and that his wife then proceeded to support the younger sons of other families through her affairs (which makes perfect sense from a financial distribution perspective, and is simply appalling from a moral perspective.) But now I have those perspectives.

The most striking and fascinating character to me was Lady de Winter, also known by many other names, who is vile to the core and seeks only for her own betterment. She's an incredible judge of character, superbly observant, and unbelievably shrewd. And she uses all her skills to serve herself alone. I enjoyed watching her mind work, especially as she found a religious target and took on the semblance of his religion to ruin him. She is a remarkable case study of the need for the spirit of discernment.

In chapter 7 Porthos, one of the three Musketeers, hires a lackey (servant) for d'Artagnan. The lackey was "found on the Tournelle Bridge, making rings by spitting into the water. Porthos had decided that this occupation was proof of a reflective and contemplative nature, and he had hired him immediately, without any other recommendation." Which tells you something of Porthos' nature, but also is foreshadowing of the usefulness of the lackey.

On page 276 d'Artagnan is contemplating Athos' person and temperament, and says he has "that unalterable evenness of temper which made him the most pleasant companion in the world." Remaining calm in cases of danger and keeping a level head in cases of excitement are both valuable. But does having an unalterably even temper make one the most pleasant companion? I don't agree with Dumas on this point.

At one point d'Artagnan is meets two women, loving one and barely noticing the other. The one he loves (Milady) disdains him; the one he barely notices (a servant) worships the ground he walks on. He asks this servant to carry a letter with awful news to Milady, and the servant runs as fast as she can to deliver it. Dumas then states "The heart of the best woman is pitiless toward the sorrows of a rival." (p.359) After pondering this for awhile, I decided that for the most part, it is true. When two women are seeking the same man, it is incredibly difficult to have charitable feelings toward the opponent.

Later on d'Artagnan's skill and value in the service of the king are noticed, and the cardinal tries to bribe d'Artagnan, offering his heart's desire (and life long goal, and father's final wish for him, etc) if d'Artagnan will leave the service of the king. D'Artagnan graciously declines. He "turned to leave, but at the door his heart almost failed him and he nearly turned back. Then the image of Athos's noble and severe face crossed his mind: if he agreed to accept the cardinal's offer, Athos would refuse to give him his hand--Athos would disown him. It was this fear that restrained him, so powerful is the influence of a truly great character on everyone around it." Enough said.

Let me return to the observation that these men are the most honorable of all, except when they're not.

Thursday, July 26, 2012

Nothing to Envy, by Barbara Demick

I really enjoyed this book and learned so much. The revelations about what life is like churned me up inside, especially when considering how the government is allocating their money. The experience of reading this non-fiction is significantly different than that of reading a novel like 1984 or Hunger Games. It's much more visceral and emotional.

The fact that most of this account has taken place during my lifetime was an interesting exercise in having a wider world-view. Considering what I was doing in my own life, how much food I had, what my education was like, etc, while those in North Korea were (and are still) suffering so desperately, was a revelation.

There is more swearing in the book than I like to read, and the subject of sex is not treated with any respect.

I liked the ending just fine, though other reviewers have disliked it. The history is still in the making. While I ache for the people who are trapped in lives of malnutrition and propaganda bombardment, I have hope for what the future will bring and know that those who have caused this misery will suffer for their actions at the hand of a perfect judge.

I recommend it.

Monday, July 23, 2012

Hondo, by Louis L'Amour

L'Amour's first novel, Hondo, was such fun to read! L'Amour is just a great storyteller. The development of the plot was fabulous and the twists of fate incorporated are enough to make a reader want to eat a book that is so delicious.

A few bits of wisdom I gleaned (L'Amour is so fond of putting this type of stuff in his books, I love it!):

To each of us is given a life. To live with honor and to pass on having left our mark, it is only essential that we do our part, that we leave our children strong. Nothing exists long when its time is past. Wealth is important only to the small of mind. The important thing is to do the best one can with what one has.

These things her father had taught her, these things she believed. A woman's task was to keep a home, to rear her children well, to give them as good a start as possible before moving on. That was why she had stayed. That was why she had dared to remain in the face of Indian trouble. This was her home. This was her fireside. Here was all she could give her son aside from the feeling that he was loved, the training she could give, the education. And she could give him this early belief in stability, in the rightness of belonging somewhere. (p290)

Saturday, July 21, 2012

A Girl of the Limberlost, by Gene Stratton-Porter

The sheer amount of emotion involved in this book was really incredible to me, and so enjoyable! It covers five years of Elnora Comstock's life and takes her through some incredibly challenging and joyful events in her life, not the least of which were high school and a courtship. Her honor and strength are beautiful. She comes to town from the Limberlost, a forest of great trees, swamps, and valuable moths.

--------------------

"S'pose we'd taken Elnora when she was a baby, and we'd heaped on her all the love we can't on our own, and we'd coddled, petted, and shielded her, whould she have made the woman that living alone, learning to think for herself, and taking all the knocks Kate Comstock could give, have made of her?"

"You bet your life!" cried Wesley warmly. "Loving anybody don't hurt them. We wouldn't have done anything but love her. You can't hurt a child loving it. She'd have learned to work, to study, and grown into a woman with us, without suffering like a poor homeless dog."

"But you don't see the point, Wesley. She would have grown into a fine woman with us; but as we would have raise her, would her heart ever have known the world as it does now? Where's the anguish, Wesley, that child can't comprehend? Seeing what she's seen of her mother hasn't hardened her. She can understand any mother's sorrow. Living life from the rough side has only broadened her. Where's the girl or boy burning with shame, or struggling to find a way, that will cross Elnora's path and not get a lift from her? She's had the knocks, but there'll never be any of the thing you call 'false pride' in her. I guess we better keep out. Maybe Kate Comstock knows what she's doing. Sure as you live, Elnora has grown bigger on knocks than she would on love." (p51)

Now some of that is good sense to me, but some of it is baloney. Allowing children to see and feel adversity and understand the world is important. But it doesn't have to come with unrighteous dominion or neglect. Loving anybody doesn't hurt them, but shielding and coddling can.

--------------------

"I am almost sorry I have these [new] clothes," she said to Ellen.

"In the name of sense, why?" cried the astonished girl.

"Everyone is so nice to me in them, it sets me to wondering if in time I could have made them be equally friendly in the others."

Ellen looked at her introspectively. "I believe you could," she announced at last. "But it would have taken time and heartache, and your mind would have been less free to work on your studies. No one is happy without friends." (p77)

--------------------

Here are the grosbeaks of which Elnora is speaking in this letter she dictates to Philip's fiance:

"I am writing this," she began, "in an old grape arbor in the country, near a log cabin where I had my dinner. From where I sit I can see directly into the home of the next-door neighbor on the west. His name is R.B. Grosbeak. From all I have seen of him, he is a gentleman of the old school; the oldest school there is, no doubt. He always wears a black suit and cap and a white vest, decorated with one large read heart, which I think must be the emblem of some ancient order. I have been here a number of time, and I never have seen him wear anything else, or his wife appear in other than a brown dress with touches of white.

"It has appealed to me at times that she was a shade neglectful of her home duties, but he does not seem to feel that way. He cheerfully stays in the sitting-room, while she is away having a good time, and sings while he cares for the four small children... I just had an encounter with him at the west fence, and induced him to carry a small gift to his children. When I see the perfect harmony in which he lives, and the depth of content he and the brown lady find in life, I am almost persuaded to buy a nice little home in the country, and settle down there for life." (p214)

--------------------

Elnora's father was a violinist and she found his violin through a neighbor in the first year of high school. She divided her practice time so that half was dedicated to playing the sounds of nature. She was a great proficient at the master's pieces, but the following description is of how she played nature after just three or four years of practice. This scene takes places in a forest "room" with trees for walls and violets as carpet. (p141, 220-221)

Elnora lifted the violin and began to play. She wore a school dress of green gingham, with the sleeves rolled to the elbows. She seemed a part of the setting all around her. Her head shone like a small dark sun, and her face never had seemed so rose-flushed and fair. ... Elnora played the song of the Limberlost. It seemed as if the swamp hushed all its other voices and spoke only through her dancing bow. ... She played as only a peculiar chain of circumstances puts it in the power of a very few to play. All nature had grown still, the violin sobbed, sang, danced and quavered on alone, no voice in particular; the soul of the melody of all nature combined in one great outpouring.

...When the last note fell and the girl laid the violin in the case... she came to him. Philip stood looking at her curiously...

"With some people it makes a regular battlefield of the human heart--this struggle for self-expression," said Philip. "You are going to do beautiful work in the world, and do it well. When I realize that your violin belonged to your father, that he played it before you were born, and it no doubt affected you mother strongly, and then couple with that the years you have roamed these fields and swamps finding in nature all you had to lavish your heart upon, I can see how you have evolved. I understand what you mean by self-expression. I know something of what you have to express. The world never so wanted your message as it does now. It is hungry for the things you know. I can see easily how your position came to you. What you have to give is taught in no college, and I am not sure but you would spoil yourself if you tried to run your mind through a set groove with hundreds of others. I never thought I should say such a thing to anyone, but I do say to you, and I honestly believe it; give up the college idea. Your mind does not need that sort of development. Stick close to your work in the woods. You are becoming so infinitely greater on it, than the best college girl I ever knew, that there is no comparison. When you have money to spend, take that violin and go to one of the world's great masters and let the Limberlost sing to him; if he thinks he can improve it, very well. I have my doubts."

...When the last note fell and the girl laid the violin in the case... she came to him. Philip stood looking at her curiously...

"With some people it makes a regular battlefield of the human heart--this struggle for self-expression," said Philip. "You are going to do beautiful work in the world, and do it well. When I realize that your violin belonged to your father, that he played it before you were born, and it no doubt affected you mother strongly, and then couple with that the years you have roamed these fields and swamps finding in nature all you had to lavish your heart upon, I can see how you have evolved. I understand what you mean by self-expression. I know something of what you have to express. The world never so wanted your message as it does now. It is hungry for the things you know. I can see easily how your position came to you. What you have to give is taught in no college, and I am not sure but you would spoil yourself if you tried to run your mind through a set groove with hundreds of others. I never thought I should say such a thing to anyone, but I do say to you, and I honestly believe it; give up the college idea. Your mind does not need that sort of development. Stick close to your work in the woods. You are becoming so infinitely greater on it, than the best college girl I ever knew, that there is no comparison. When you have money to spend, take that violin and go to one of the world's great masters and let the Limberlost sing to him; if he thinks he can improve it, very well. I have my doubts."

Labels:

Education,

Friendship,

Middle-Grade,

Nature,

Parenting,

Read Again,

Read more of this author

Tuesday, July 17, 2012

The Lonesome Gods, by Louis L'Amour

----------------------

A copy of the Illiad [lay] on the table. "You are reading this?" he asked.

"I have read it many times. Now I read it to my son."

"But he is too young!" The man protested, almost angry.

"Is he? Who is to say? How young is too young to begin to discover the power and the beauty of words? Perhaps he will not understand, but there is a clash of shields and a call of trumpets in those lines. One cannot begin too young nor linger too long with learning.

"Homer told his stories accompanied by the lyre, and it was the best way, I think, to tell such stories. Men needed stories to lead them to create, to build, to conquer, even to survive, and without them the human race would have vanished long ago. Men strive for peace, but it is their enemies that give them strength, and I think if man no longer had enemies, he would have to invent them, for his strength only grows from struggle."(p116-117)

----------------------

I had learned that one needs moments of quiet, moments of stillness, for both the inner and outer man, a moment of contemplation or even simple emtiness when the stree could ease away and a calmness enter the tissues. Such moments of quiet gave one strenfth, gave one coolness of mind with which to approach the world and its problems. Sometimes but a few minutes were needed.

Long walks can provide this, or horseback rides, reading a different book, or even just sitting. Here, in the pleasant coolness of this galeria, listening to the waters of the fountain, I could gather my forces again, and perhaps reach some conclusions about myself. (p306-307)

----------------------

This was the good life, this I could do, ... and perhaps have a little to do in shaping the destiny of our country.

For it is not buildings that make a city, but citizens, and a citizen is not just he who lives in a city, but one who helps it to function as a city. My father had often talked of the town meetings in New England and of the discussions that helped to shape the destinies of cities and states. For this I must prepare myself, for I knew too little of law, too little of governing, too little of the conducting of public meetings.

There is no greater role for a man to play than to assist in the government of a people, nor anyone lower than he who misuses that power. (p 308)

----------------------

Changing tracks to President Hinckley now, a prophet of our Heavenly Father:

You need time to meditate and ponder, to think, to wonder at the great plan of happiness that the Lord has outlined for His children. You need to read the scriptures. You need to read good literature. You need to partake of the great culture which is available to all of us.

I heard

President David O. McKay say to the members of the Twelve on one

occasion, “Brethren, we do not spend enough time meditating.”

I believe

that with all my heart. Our lives become extremely busy. We run from one

thing to another. We wear ourselves out in thoughtless pursuit of goals

which are highly ephemeral. We are entitled to spend some time with

ourselves in introspection, in development. I remember my dear father

when he was about the age that I am now. He lived in a home where there

was a rock wall on the grounds. It was a low wall, and when the weather

was warm, he would go and sit on his wall. It seemed to me he sat there

for hours, thinking, meditating, pondering things that he would say and

write, for he was a very gifted speaker and writer. He read much, even

into his very old age. He never ceased growing. Life was for him a great

adventure in thinking.

Your needs and your tastes along these lines will vary with your age. But all of us need some of it.

----------------------

It seems that Louis L'Amour had a great deal figured out correctly.

Labels:

Drama,

Education,

Friendship,

Nature,

Parenting

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)